The Cunningham Clan Comes West

On April 17, 1848, the Williamson family, which had been on furlough in Ohio since fall of 1847, left Ripley, Ohio, and began their journey back to Kaposia village in Minnesota. With them were Sylvester Cook, who was coming out to Kaposia as a teacher; and Miss Martha Ann Cunningham, who was embarking on a two-year commitment to the Dakota Mission.

This might be Martha Ann Cunningham; image is from the famous Ebell escape photo taken on August 20, 1862.

Martha was the daughter of William and Ellen Doak Cunningham. She had eleven brothers and sisters and was fifth in the family, born on December 20, 1819. In the culture of 19th century Ohio, a woman like Martha, who was already twenty-eight years old when she came to Minnesota, would have been considered a spinster. The opportunity to venture west was perhaps her last opportunity for some exciting new experiences before she settled into life as a single woman.

There is not a great deal of information about Martha in the source documents of the ABCFM. Thomas Williamson wrote to S. B. Treat at the mission board on April 19, 1848 to inform him that they were bringing Miss Cunningham out to Kaposia. On June 5, 1848, he informed Treat that they arrived home on May 5, 1848. He said,

“Miss Cunningham is helping Jane with teaching the girls. She came out at the Board’s expense. She might stay two years. She remains very usefully employed which helps Mrs. Williamson and my sister, who have been in poor health. Once they are well, she will go to one of the Ponds.”

That happened by October 20, 1848, when Samuel Pond wrote to Treat, “Miss Cunningham, a young lady who came out last spring with Dr. W. has come to reside with us so we are no longer destitute of a teacher.”[1]

Jane Williamson appreciated Martha even during the journey from Ohio. She wrote to Elizabeth Burgess on June 9, 1848:

“I scarce know how we should have done had not the Louis included Miss Cunningham to come with us. We would feel it a great privilege to have her remain with us but as she is much needed at some of the other stations. If sister should continue better perhaps we ought not to wish it. She will be better and useful at either of the stations.”[2]

Martha stayed with Samuel Pond’s family at Shakopee until the spring of 1849, when she was to go to Traverse des Sioux and help Robert and Agnes Hopkins with the mission and school there. In July of 1849 Robert Hopkins wrote to S.B. Treat that he, Mr. and Mrs. Moses Adams, Miss Cunningham, and a number of Indians were leaving for Lac Qui Parle. Martha was assigned there to assist Mary Riggs.[3]

In her memoir, A Small Bit of Bread and Butter, Mary Riggs wrote that:

“When Mr. and Mrs. Adams returned here a Miss Cunningham from Ohio accompanied them. She has been at Mr. S.W. Pond’s during the past winter and is now with us. I cannot but hope her stay with us will be a blessing to us all. I believe she intends returning to Ohio in the fall.”[4]

Martha did return to Ohio sometime in 1850; unfortunately I have not found any mention of her departure but it is interesting to note that she was back in Minnesota in 1862 when the U.S. Dakota War broke out on August 18, 1862. [5] By that time, Martha was married and had two little boys. Her husband was James Brown Rogers, who had been married to Martha’s sister Jane Cunningham Rogers from 1835 to1843, when Jane died, leaving an eight-year-old son, William Rogers, who was killed in the Civil War on September 11, 1864. James Rogers remarried to Nancy Ruder in 1846 and they had one daughter named after Jane, who was born in 1847. Nancy died six months after Jane was born on July 26, 1847.

When Martha Cunningham returned from Minnesota, she must have connected with her former brother-in-law, James Rogers, who was living in Indiana with his children from his first two marriages. William Rogers was Martha’s stepson and nephew and he was already eighteen years old when Martha and James were married. Jane was Martha’s stepdaughter from James’ second marriage and she was five years old when James and Martha wed in Tippecanoe, Indiana, on April 14, 1853. Their first child, Edwin Cunningham Rogers, was born on April 27, 1857 and their second son, Franklin P. Rogers, arrived on September 8, 1860.

Hugh Doak Cunningham was with the group that escaped Hazlewood on August 18. His two sisters and wife were also with the group. This image is cropped from the famous Ebell escape photo taken on August 20, 1862.

By that time, Martha’s brother, Hugh Doak Cunningham, had followed in her footsteps and come out to Minnesota in 1856 to work with Stephen Riggs at the new mission at Hazlewood. Hugh was thirty-four years old when he arrived in Minnesota. He had never married but must have graduated from some type of academy or seminary in order to be qualified to be a teacher and leader at the mission.

Hugh met Mary Beauford Ellison shortly after he arrived. Mary was just one of several Williamson family relatives who spent time working at the mission in Minnesota. She came out in 1856, but two of her brothers were among the first Williamson relatives to join the mission when the Williamsons were stationed at Kaposia. John Calvin Williamson and his brother, William Williamson Ellison, came to Minnesota by 1849. John was born on June 22, 1820 , and William on February 22, 1822. Their parents were James and Mary Beauford Williamson Ellison. Mary was a half-sister of Thomas and Jane Williamson, their father’s daughter by his first wife. For the Thomas Williamson children, Mary and James Ellison were their aunt and uncle and their children were their cousins. Mary Ellison died in 1835 when John and William were fifteen and thirteen years old respectively. Their seven additional brothers and sisters ranged in age at that time from seventeen to four years old.

Mary Beauford Ellison married Hugh Cunningham in February 1857 in Minnesota. This image is also from the Ebell photo of the escape group on August 20, 1862.

John Ellison was at Kaposia with the Williamsons in 1849 when Alexander and Lydia Huggins came to the village to pick up their three oldest children who had been living with relatives in Ohio. When they returned to their home at Traverse des Sioux, they had a young man with them from Ohio, “an American named Ellison of a good family” Unfortunately the young man got knocked out of the boat and lost his glasses which was a serious problem since spectacles were hard to replace.[6]

William and John Ellison are both listed in the 1850 census at Big Stone Lake and Crow Village (Kaposia). Interestingly, John Poage Williamson, Thomas and Margaret Williamson’s oldest son, is listed in the census of 1850 in Sprigg, Adams County, Ohio, with William and James Ellison’s sister, Elizabeth Ellison Livingston, and her husband, Samuel Livingston. John Williamson was fifteen years old and was attending school in Ohio. The Livingstons lived at Jane Williamson’s childhood home, The Beeches, from 1843 until Jane sold the property in 1856 so John Williamson had the opportunity to live in his grandfather’s home where his own father had grown up.

William Ellison reportedly attended school at Kaposia when John Aiton was the government teacher there although he was nearly 30 years old. He is enrolled from October to December 1851 and June to March 1852.[7] That summer he was sent to the new Williamson mission site near the Upper Sioux Reservation to build the new house and mission there. Jane Williamson reported to her cousin, Elizabeth Burgess, about his work on the house in a letter dated November 19, 1852.

This is the only known image of the Williamson House at Pejutazee which William Ellison and his crew of workmen built in 1852.

“We arrived here Sat. evening. The next Tuesday morning Wm. Ellison and J. P. W. started down the former for Ohio. John and Andrew probably went to Galesburg, Illinois (Amos Huggins is there) but do not know certainly where they are. John had not entirely concluded when he left us and we have received no mail since we came here.”[8]

William Ellison escorted John Williamson to Ohio, but returned to Minnesota and continued to help with construction at the new Williamson mission site known as Pejutazee and with the Riggs mission at nearby Hazlewood. He married Sarah Rebecca Pond, the third child of missionaries Gideon and Sarah Poage Pond, on May 10, 1859. Sarah had been born in 1842 at the Oak Grove mission in Bloomington, William was twenty years older than Sarah but they wed and had seven children between 1860 and 1880. William was fifty-eight years old when their youngest, Ruth Edna Ellison, was born on September 27, 1880. William and Sarah spent their lives in Bloomington, Minnesota, but William also invested in property in and around St. Peter or what was then Traverse des Sioux, Minnesota. In 1856 and 1857, he gave Thomas and Jane Williamson several properties, which is where they ended up living after the outbreak of the U.S. Dakota War of 1862.

William’s brother, John Calvin Ellison, who had been with him at Kaposia in 1850, married Lydia Lockhart in Greene, Ohio, on March 9, 1852, but they returned to Minnesota and settled in Traverse des Sioux (now St. Peter, MN) where they raised their three children, James Ellison, David Ellison and Ada Ellison. Lydia passed away in 1874 at the age of forty-nine and John relocated to Missouri and then to Kansas where he passed away at the age of 94 in 1914.

William and John’s father, James Ellison, had been a widow for many years and he moved to be near William, John and Mary by 1875, when he is listed in the census at Traverse des Sioux at the age of eighty-eight years. He became acquainted there with Jane Williamson, and was known to be very helpful to her when her eyesight began to fail in 1880. I have not found a date of death for James Ellison but he was born in 1787 and was still alive in 1883 so he was well over ninety years by that time.

We first meet William and John’s sister, Mary Beauford Ellison, in a letter that Rev. Stephen Riggs wrote to S.B. Treat of the ABCFM on March 4, 1856. He told Treat that “Miss Mary Ellison has been teaching for 7 weeks and attended to the girls sewing in the afternoon.”[9] Mary was thirty-eight years old when she came out to join her brother William at Yellow Medicine. From everything I have found in the source documents, Mary Ellison was not a missionary with the ABCFM. It appears that she may have come out to assist Mary Riggs at Hazlewood by teaching the Riggs own children and helping teach the Dakota girls and women skills like sewing.

In any case, Mary met Hugh Doak Cunningham at Hazlewood and they were married in 1857, either at Hazlewood or, as other records indicate, at Traverse des Sioux. Hugh and Mary Ellison Cunningham began their work at Hazlewood with Stephen and Mary Riggs in 1858. They were to be paid $350.00 a year and their board; but furnished their own bedroom. On June 12, 1858, Stephen Riggs told Treat that if they were good, he would expect the ABCFM to hire them and take responsibility for the school. [10]

Mary Huggins Kerlinger, writing in her journal in 1861, said:

“I came down that time with Mr. Cunningham manager of the boys boarding school must say here I do not think a more able pair for that work could have been found than he and his wife. They loved the children and exercised a wise and kindly discipline and the children loved them and improved rapidly.” [11]

It is important to once again say here that the use of the term boarding school by Stephen Riggs and the ABCFM should not be associated with the horrific history of the federal government’s Indian boarding schools of the 1870s-1960s. Dr. Thomas Williamson always refused to even consider running or being part of a boarding school because he had promised the Dakota people years earlier than he would never use the education funds provided to them under treaty for such a purpose. Stephen Riggs believed that the Dakota boys and girls would get the best education and access to opportunities if they lived under the same roof for months at a time and although he always encouraged the students to use the English they had learned, the Dakota mission had always stressed that learning to read and write in Dakota took priority at all age levels.

Mary and Hugh taught at the Hazlewood Mission from 1858 until 1862. This photo is one of the only images of the facilities that survived the war of 1862.

On February 12, 1859, Hugh wrote to S.B. Treat at the ABCFM asking that he and Mary be appointed as official assistant missionaries. He said that they had some scruples because of the board’s stance on slavery but decided that it would be best. They were appointed by March 9, 1859. Treat wrote to the Dakota Mission that “Mr. Cunningham will be recognized as a member of the commission with all the rights of the older brethren.”[12]

A small window into daily life at the school is provided in letters that Thomas Williamson sent to Selah Treat of the ABCFM in 1860. On July 20, 1860, Thomas mentions that,

“Mr. and Mrs. Cunningham are so dissatisfied with Annie Ackley’s teaching they are threatening to leave and it would be very hard to replace them as the behavior of the children is improved since they came and the children love and respect them.” A few months later, on November 23, 1860, he reported that, “Mrs. Cunningham became ill and Mrs. Ackley took over all the kitchen and sewing work and gave up teaching which she did for several months without complaint. Mr. C. failed to get help for his wife which made this necessary. Both Mr. and Mrs. C. are grieved that the children aren’t making more progress and they are finding it difficult sustain their family on their allowance. They have been successful in teaching the children to speak English.”[13]

Emma Cunningham was 26 years old when she came out to Hazlewood to visit her brother Hugh and his wife Mary. She got caught up in the outbreak of the war and had to flee with the Riggs escape group. This image is another from the famous Ebell photo of that group.

Hugh and Mary Cunningham were working at Hazlewood when Hugh’s youngest sister, Marjorie Emma Cunningham, always known only as Emma, came out to Minnesota to help them in October 1861. Marjorie was twenty-six years old and she recorded her experiences in her journal from October 25, 1861 to May 2, 1863. Her observations about the other teachers at Hazlewood, her record of her daily activities and social outings, and her reflections on her adventure are filled with details of life at the mission.

One of her journal entries recently provided new information to today’s members of the Williamson family. The date of Martha Williamson Stout’s wedding was never recorded in any of the family tree information. But Emma’s second entry in her journal on October 28, 1861, records that Emma attended Martha’s wedding to William Stout at Dr. Williamson’s home that very morning and that Hugh Cunningham took the newlyweds to Traverse des Sioux immediately after the wedding as they were headed for Ohio.[14]

One of the more significant passages in Emma’s diary covers the weeks just prior to the outbreak of the U.S. Dakota War. I have included Emma’s entries and some additional notes to clarify individual names and places.

“8/5/1862 – Some of the folks were very much frightened today about the Indians going to fight the white people. The difficulty arising about the Indians having to wait so long for payment but altho there is some danger of trouble quiet was restored by evening all was peaceable.

8/7/1862 – 11th anniversary of dear pa’s death. (Pa” is William Cunningham, 1790-1851)

8/8/1862 – We have taken a boarder for a few days. He is an artist and has the use of two rooms. (This could very well be Adrian J. Ebell, who was a photographer who had come to the Upper Sioux Agency to take general photographs of the Dakota and the mission activities in August of 1862s. Ebell’s photographs from August 17, 1862, the day before the war began and from the Riggs party escape are among the most famous and all have been used in Dakota Soul Sisters.)

8/10/1862 – When we got up in the morning, Doak went out to the stable and found Charley and Frank stolen. Some Indians broke the lock and broke the door down. (Emma always calls Hugh by his middle name of Doak.)

8/11/1862 – Just as breakfast began we were called to the door and there was Frank. Some Indian brought them back.

8/13/1862 – We were to have gone this morning to get our pictures taken but it rained and we did not get off until 11 o’clock we got the little boys and Jenne’s but not the rest of us.

8/14/1862 – Went back to the Agency and got our pictures – Doak’s and Mary’s are very good but I don’t like mine. After dinner, Mary and I called on Mrs. Givens and Mrs. Wakefield. (This indicates that Ebell was indeed taking photos of the individuals at the mission. Unfortunately, no known photos of the Cunninghams have ever been found. No doubt they were destroyed in the vandalism and destruction that took place during the war.)

8/18/1862 – Mrs. Pettijohn and her child came down in the afternoon on the way to Traverse des Sioux. Just as we were eating supper, word came that the Indians had killed some white people at the Lower Agency. Soon the children’s parents began to come and take them away. Some frightened almost to distraction and urged to gather up and make our escape immediately. We retired but had not gone to sleep when we got word again that the Indians from above us and below us were preparing to make the attack about daylight. Our friendly Indians said we must go immediately. We did so. Mr. Riggs family and ours with Mr. Pettijohn. The Indians piloted us about 5 miles up the river and took us over the river in a canoe. Left us on an island where we were to hide in the bushes all day and when dark came they were to assist us to get away. In the meantime, Mr. Hunter had got his family over the river and had his two teams. My brother and Mr. Pettijohn went to try and get our teams and the rest of us started with Mr. Hunter’s folks. My brother and Mr. P got only one of his horses and a buggy. The Indians would not let him take the other. We traveled briskly and stopped and laid down overnight. (The Pettijohns are Jonas and Fanny Huggins Pettijohn and their daughter Alice, who was eight years old. Marjorie does not mention Jonas and Fanny’s sons William, who was ten years old, and Albert, who was twelve. Mr. Hunter is Andrew Hunter who is on the escape with his wife, Elizabeth Williamson Hunter, their two children, Nancy, aged 3 and John, who was just eleven months old; and Elizabeth’s sister, Nancy, aged 20, and her brother, Henry who was 11.)

8/20/1862 – Cooked some meat and bread. (This is her entry from the day Ebell took the famous escape photograph.)

8/22/1862 – We stopped about 15 miles above Ft. Ridgely and saw Dr. W and his family approaching. They had left the night after we did and got on the trail.

8/22/1862 – Andrew said they couldn’t get in the fort.

8/23/1862 – In the afternoon we came to the first house we had seen since we started. It was deserted people had left in confusion – went on mile after mile. Stopped at another deserted house and camped until morning.

8/25/1862 – We were still 12 miles from Henderson. Mr. Riggs family went to Henderson – the rest to St. Peter. We got there after dark. Place filled with soldiers and all rejoiced to learn we were alive. Doak, Mary and I spent the night at Dr. Daniels. (Both Asa and Jared Daniels were doctors and brothers. I don’t know which one might have had a home in St. Peter in August of 1862, since both were working at reservations at that time.)

8/26/1862 – Mr. Livingstone from Mpls was in St. Peter. Mary and I came away with him we traveled as far as Belle Plaine.

8/27/1862 – Got to Shakopee and had dinner at Samuel Pond’s where we met with the rest who had left us on Monday. Got to Mpls. that night – arrived here about midnight.

8/28/1862 – Too tired to get up

8/30/1862 – Mary and I went out shopping. Gideon Pond and John Williamson took dinner with us. (Apparently John P. Williamson, who had been away from the agency when war broke out, had returned from Ohio and was having dinner at Oak Grove in Bloomington, Minnesota with Gideon Pond, Emma Cunningham and Mary Ellison Cunningham.)

9/2/1862 – It is one year since I left home to come to MN. Mr. Riggs came to call. I expect to go in company with him and his sister as far as Chicago on my way home.

9/4/1862 – After dinner Doak took me down to St. Paul. I took the boat in the evening. Started home in the company of Alfred and Anna Jane Riggs. (Alfred and Anna were on their way back to their schools in the east.)

9/5/1862 – Stuck on a sandbar 15 miles from St. Paul.

9/6/1862 – Got to Prairie du Chien – took the cars to Chicago.

9/7/1862 – Got to Chicago at 6 am – put up at Biggs House. Alfred went to church – Anna and I laid down. In the evening we attended a large union meeting held for the purpose of taking measures to send for a memorial to the president on behalf of freeing the slaves immediately.

9/8/1862 – Got home – reached Logansport. (Logansport, Indiana)

5/2/1863 – Mary and Doak are in town.”[15]

This photo of Emma Cunningham Shultz was taken when she was a much older woman living in Iowa where she and her husband, John Shultz settled.

What makes Emma’s brief diary of special interest to researchers is the fact that she had not been identified for many years as one of the women who were part of the escape party on August 19, 1862. She just happened to be in a very wrong place at a very wrong time. After Emma got back to her family in Indiana, she married John Baughman Shultz on June 1, 1867, in Lee County, Iowa. They had communicated by mail while John served in the Civil War but there is no indication of how or when they met. They had two children, William, born in 1871 and Laura, in 1874. Emma was eighty-three years old when she died on June 20, 1917, in Cass County, Iowa.

Hugh Cunningham wrote an eloquent and detailed account of how he and Mary fled Hazlewood on the night of August 18, 1862. He recalled how the community around the mission became anxious and excited as news of the Indian attack on the Lower Sioux Agency spread. Many of the Dakota urged the Cunninghams to flee and the parents of the children in the school began to arrive to retrieve their sons and daughters while urging the missionaries to get to a place of safety. Hugh wrote:

“The first thing that convinced the more unbelieving ones of us of the reality of our danger was the stealing of Mr. Rigg’s [sic] horses and wagon from Mr. Pettijohn, some two miles from our place, who was moving his family to Saint Peter. During the evening and fore part of the night the excitement seemed to increase. The Christian and Friendly Indians gathered about our houses and offered to protect us all they could, but said they were but a few when compared to the others. We felt as though we didn’t like to expose them, to protect us when the odds seemed so much against us. They all gave one voice, and that was to get to a place of safety. We had, during the night, seen some of those who had come in, of the baser sort, trying to get the horses out of my stable, while that had taken several in the neighborhood. It was evident about midnight that the best thing we could do was to put ourselves under their care, follow their advice and the sooner the better.

“About one o’clock A.M., we left our homes, never to return. When we started we had but one two-horse team and a single buggy to carry twenty-two persons, mostly women and children. Some of our company thought we had best not try to take my horses as they would probably be taken from us. But we thought that we would only have to walk if they did, and we should start with them anyhow. Some of the Indians went with us as guides and guards. We followed them through the timber about three miles, to an Indian village, where we found some of our neighbors who had started before us. After a long council it was decided that we had better conceal ourselves on an island two miles from the village and wait till the next night before we went any further. This not at all agreeable to our feelings, but we submitted.

“Two men went with and ferried us across to the island in a canoe that would only carry about two persons beside the one who paddled it, at a time. We were all over in safety about daylight. When we got to our place of concealment we felt as though the flesh was weak indeed, and that is was necessary to rest if we could, which was a very difficult matter among the swarms of mosquitoes that infested the place. After an hour or so spent in our vain endeavors to court sleep, we gave it up; we arose and read a portion of scripture and committed ourselves to the keeping of Him who alone could grant us deliverance in such a time of distress.

“After so doing we partook of some refreshments, which consisted of about three small crackers, as our desire for food seemed to have left the most of us. The supply for the whole party was about three of four quarts of said crackers, but the Lord who fed the five thousand with but little more bread than we had could feed us also. Soon after we had thus refreshed ourselves, an Indian woman came with some forty or fifty pounds of provisions sister E______ had prepared and we had forgotten to take with us in our haste to be gone.

Rev. Stephen Riggs organized and managed the escape of forty-some individuals who fled from the Hazlewood mission and tried to reach safety at Fort Ridgley on August 18, 1862.

“Mr. Riggs and myself visited the village early in the morning where we learned that the work of destruction had commenced at the Agency, five miles from our homes, and that our houses had been rifled also. We soon returned [to] our hiding place, where we spent the forenoon in great anxiety, drenched with the rain and tormented by the mosquitoes.

“About one o’clock P.J., Mr. Riggs returned the second time from the village, with the painful news that the man he had left his horse with had refused to give him up, having heard that the owner had been killed, as he said, and he thought he had as much claim to him as anyone else. We immediately began to prepare for our departure. While the rest of the company were removing from the island to the other side of the river, Mr. Pettijohn and myself made another visit to the village to get my horses and secured one of them.”

Hugh goes on to report that the group on the island ran into Andrew and Elizabeth Williamson Hunter and their children who were traveling with two other families from the mission. He was unable to catch up with them as a violent rainstorm prevented him from following their trail and he spent the night on the open prairie with the Dakota man who had been caring for his horses. Late the following afternoon three Germans joined them. They had left the group that was being led to safety by John Otherday. They rejoined the group from the island later that day. The story continues:

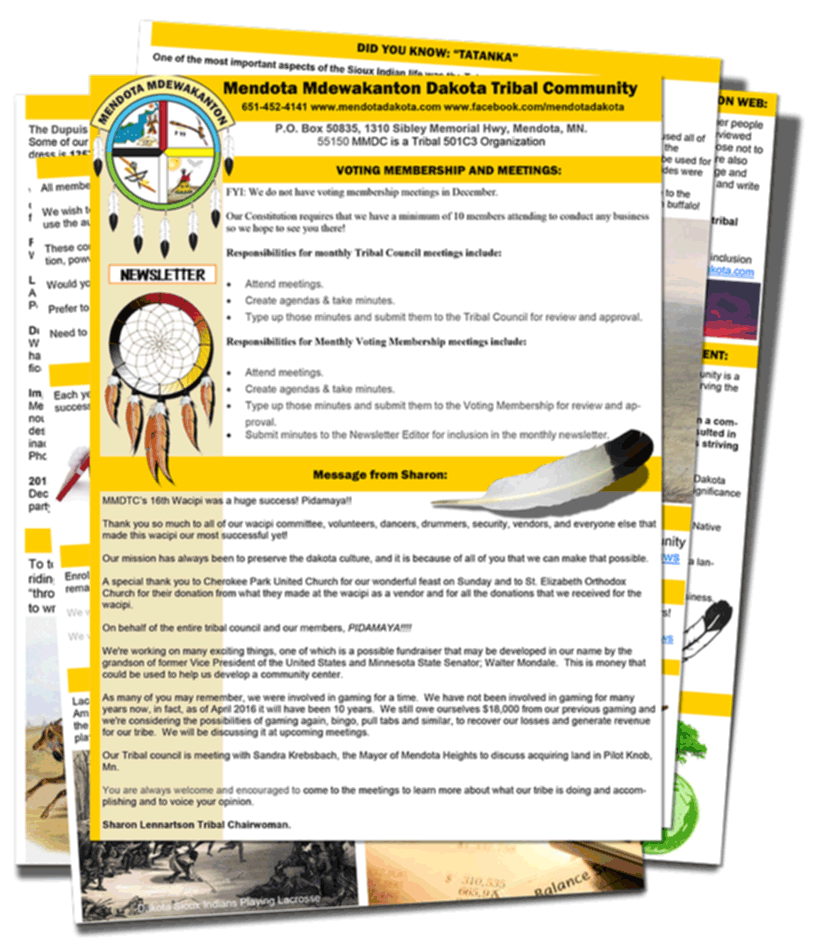

This is the famous Ebell photograph taken of the group that was fleeing the Hazlewood mission in August 1862 with assumed identifications, including women’s eventual married names, all birth/death dates and ages at the time of the escape. Hugh Cunningham said that there were 42 people in the group by the time they reached the fort. There are fewer identified people in the photo but it is reasonable that some of them, especially the young boys, were not there for the photographer.

“Our company now numbers forty-two. The night passed slowly away to many of us. It rained the whole night, and until ten o’clock A.M. We started again, after committing ourselves to the guidance of Him who alone could guide in the path of safety. Cold, wet and hungry, we traveled until noon to get to a grove some ten miles from us, and then had to stop two miles from it. Dead Wood island is surrounded with a marsh and some lake. Six others and myself went forward, I leading the way through grass higher than our heads and water to our knees a good portion of the way. By the time we returned, some of the others had butchered a calf and many of the juveniles were soon roasting or warming meat on a stick and eating it. We passed the afternoon at this place and started the next morning, somewhat refreshed.

“At noon we stopped at Birch Cooley, about five miles from the Lower Agency, where we were joined by Dr. Williamson, wife and sister. We then learned that we were in the midst of danger. When the first part of the Dr.’s family started, he was determined to stay and see it out. Said he was willing to die then if it was the Lord’s will. Sometime the next night he started, accompanied by several of the Indians who had stayed by him the whole time guarding him and his property as best they could. After a short rest and consultation, it was decided to reach Fort Ridgley that night, which was some fifteen miles distant – at that time surrounded by the hostile Indians. This was somewhat of an undertaking, with worn-out ox teams. Some distance above the Fort evidence of the work of destruction which had been done and was still going, began to increase. About five miles about the Fort we passed the remains of a dead man.”

Picture depicting Fort Ridgley in 1862. Hundreds of refugees from the war tried to find safety at the fort but many, like the Riggs group, were turned away for lack of room and provisions. Creator: Paul Waller Photograph Collection ca. 1862 Location no. MN2.7F p40 Negative no. 13718

Hugh explains that when they came near the Fort, Andrew Hunter crawled on his hands and knees until he got inside and spoke with the commander who advised him to keep going and try to make it to Henderson because the fort was full of refugees and in danger of being attacked again. He returned to the group with this news and the party argued about what they should do. The Dakota that had attacked the fort were camped less than a mile away so at ten o’clock that night, the group got moving again, leaving the road and going across the prairie until two o’clock in the morning when it was too dark for them to see. Hugh continues:

“About nine in the morning we stopped for breakfast, and to rest our worn –out teams. At one o’clock P.M. we stopped at the first house we came to, where we spent several hours refreshing ourselves. We traveled that night until eleven. As we had been during the day, were still in sight of the burning buildings. The next morning being the Sabbath we were a little later in starting that usual. We had now reached the settlements, but the settlers had all fled.

“We traveled that afternoon only about six miles, when we reached a place where there were a number of settlers collected to protect themselves. We stopped near them, having heard that reinforcements had past [sic] on their way to Fort Ridgley. In the afternoon we had religious services, and O, what a precious season that was. We felt that we had been under the special care of Providence, that we had put our trust in Him and had been so far delivered.

St. Peter, Minnesota, was not a bustling commercial center in 1862 when hundreds of refugees poured in seeking safety in 1862. This photo of the downtown was taken in 1867.

“The next morning, after having spent a week together in the most trying circumstances, we separated, never to meet again in this world, some of us going to St. Peter, and others going to Henderson, St. Paul, and further on, we going with the former party. We reached our place of destination sometime after dark, weary and worn, without anything of this worlds goods but what we had worn away.

“Then and not until then did we realize the danger to which we had been exposes, and what a signal deliverance the Lord had granted us while so many other had met with a worse fate.” [16]

Hugh and Mary Cunningham joined John P. Williamson and Bishop Henry Whipple at Fort Snelling to assist in bringing Christianity to the Dakota who were being held there in the aftermath of the war.

Hugh and Mary stayed with friends in St. Peter for the weeks following the end of the war in September 1862. They also traveled to St. Paul once the Dakota women and children and men who had not been found guilty in the trials of early October were relocated to Fort Snelling. There they assisted John Williamson with the ministry to the Dakota in the encampment. In May of 1863, the Dakota at Fort Snelling were moved from the encampment to the new reservation at Crow Creek, South Dakota. John Williamson accompanied them and was to be the lead mission worker there. Hugh and Mary wanted to go out there to assist him in his work but had to wait until hearing from the ABCFM as to where they would be assigned.

On November 10, 1862, both Hugh and Mary testified that Thomas Williamson’s claim for his family’s losses in the war was accurate. In December Hugh wrote to S.B. Treat to tell him that he wanted to open an Indian boarding school near Gideon Pond and needed the $1,000 that Stephen Riggs had asked the board for. Treat responded that he didn’t think it was wise to open a new school anywhere in Minnesota until they learned where the Indians would be sent.[17]

Hugh wrote to Treat again from Minneapolis on February 6, 1863. He shared that they didn’t know where they were going to live and that they had two Dakota girls with them and expected to take Simon Anawangmani’s son with them when they left. They said they would leave him with his brother-in-law where he would be under good influence. Treat advised Hugh to submit a voucher for payment of his salary and expenses from July 1, 1862-October 1, 1862, and to mention that the school had ceased operation on August 19, 1862 because of the war.[18]

John Williamson had some concerns about their plans. He wrote to his father.

“Mr. and Mrs. Cunningham are already connected with the mission and it would seem more appropriate that they should come but I don’t think they would want to come to teach such a school and if they did they would be suited to the place. We want to teach Indian here and they don’t understand it enough to teach it well. I don’t think that cousin Mary’s health would stand it.”[19]

Mary and Hugh Cunningham worked with John Williamson at the Crow Creek reservation in South Dakota from 1863 until 1864. The Dakota were moved to a new and much better area in Niobrara, Nebraska in 1866.

Later that spring, still without a new posting, Hugh and Mary made a visit to Illinois. They planned to visit friends and family and raise money for what they hoped would be a new mission. They returned to Minnesota, and although they had not received official permission from the ABCFM, they made the journey out to Crow Creek, South Dakota, where John Williamson was heading up the new mission and school at the reservation there. John Williamson wrote to his father on December 14, 1863, and said that Hugh and Mary were teaching about thirty students in English while Edward Pond has enrolled 131 students in Dakota school.[20]

Conditions at Crow Creek were deadly for the Dakota with many dying of illness and starvation. The land was not suitable for farming and there was no game nearby. Many of the missionaries began to complain to the government that the place was completely unsuitable and to petition for a reservation in a better location.

Hugh and Mary also had to leave for a time to take part in their own hearing concerning what kind of settlement they were to receive from the government for their losses experienced as a result of the war. The hearing took place at St. Peter, Minnesota on September 13, 1864. Hugh and Mary were seeking compensation of $$3,310.83 and Stephen Riggs testified on their behalf. He told the court that the Cunninghams’ house had been completely destroyed, burned down with all the buildings at Hazlewood by the Indians.

Hugh himself testified that they had lost everything owned and had only retrieved one horse and buggy after the war but that the horse had been so misused that it was worth little and the buggy was worth no more than $25.00 in its damaged condition. He also mentioned that his sister Marjorie had included $120 or $130 worth of items, all clothing, that she had lost in the war. After describing the furniture and carpeting that had been in their home, he and Mary submitted the following:

“p. 10 The wash bowl & Pitcher was large stone Cantesnumerate (sp?) Crockery

Item 99 cost amt charged in Cincinnati

Some of the books his father had, the others were mostly new.

Had the dress coat 2 years, cost $18 or$20

Had one of overcoats 5 years but seldom wore it – had wore out 2 others in the time

Some of the shirts were half worn – Had two pair woolen shirts and 2 pr drawers – Most of the Window Curtains were curtain calico

The Cupboard was Basswood, with paint worn off 3 x 4 with door 4 shelves

Kept a lot of thimbles for the indian [sic] Girls to sew with: had been in the habit of keeping a lot of such things on hand as the Squaws were constantly coming there and offering to work for such things 0-

The bill of Dry Goods is estimated – they were turned over by the Department for the use of the Indian Children as their share of the annuity Gods, and belonged to them as such

Items from 95 to 302 were purchased by me for the indian children, intending to draw their money annuities to pay for them – but the outbreak occurred before the payment consequently I never did. I had paid for them.

The Pork was salt about 1/3 of the bbl had been used

The “Childrens Clothing and Girls Clothing”

p. 11 come under the 2nd Exception before referred to –

Our fiscal year ended in December. We had made the estimates for that year at the October previous. It amount to $1,150.00 and it was allowed by the Board. This was for the Boarding School alone – and had drawn about $570 of it – Most if not all of the clothing had been purchased or made since the preceding fiscal year – and some of it had been dealt out to the children and worn by them – At the time of the outbreak there were 11 children in the school and boarding with me.

Had about 5 acres under cultivation – about 4 acres of potatoes, ½ acre beans, acre corn, ¼ acre rutabagas and a patch of peas.

The Garden was about 1/3 of an acre – with raspberries set on three sides, thinks there were 100 of them, some been set 2 and some 1 year, about 75 strawberry plants, and about 50 Gooseberry bushes.

H.D. Cunningham

Mrs. Mary B.E. Cunningham

Being duly sworn says she is wife of claimant and at the time of outbreak was living at Hazlewood, and assisted to make the Schedule attached to his complaint (and being particularly interrogated as to the articles in Schedule says)

As to items 1-4-5, 20 to106; 108 to 159 to 161 to 322

p. 12 325 to 373 & 380 she knows of her own knowledge and can describe them as to quantity and quality – but as to the other items she knows they had articles of the kind but cannot speak the number of value thereof.

That she escaped with her husband and all the property was left behind –

That the prices charged for the articles she knows are no more than they were worth then and there –

Cross Examined

The witness being interrogated at length as to the Schedule among other things said,

That the Feather beds would not weigh less than 25 lbs each as she believes,

One of item (44) was about 5 yards long, one 4 and one 3-1/2 – item 45 were about same size

The Sheets were all for double beds

Item 50 were larger but plain – The Velvet bonnet was new – it belonged to my sister. The Silk had more than a year. The Crape [sic] Shawl cost $14, 12 years before but was as good as new – The Bracket cost $15. One of the silk dresses was black – had it 4 or 5 years the other a fancy one, almost new belonged to my sister

The Wood delain was almost new

Had the Poplin and Ginghams a year –

Sister left 2 calico dresses which are not in the bill

p. 13 Had the quilted S____ a couple of years

The number of yards of Dry goods charged and estimated – they had several whole pieces of Goods – thinks they had 4 pieces of Calico –

Thinks they had more than charged as there were several remnants which she forgot when the bill was made. Had 40 yards of one kind of Gingham

2 dress patterns of another and some remnants

Had 2 whole piece Bleached Muslin, and remnants of 3 others – Had more than 2 dress patterns of Debayr, (sp?) and one whole piece of one kind of ________ and parts of three others colored,

All the goods turned over by the department and comprised in items 258 to 272 inclusive

Had 2 entire pieces of Bleached muslin and remnants of several which with made more than one full pieces- Thinks they had over 50 yards of Delaine

Item 313 had not been worn at all

The Feathers were indian feathers.”

In the end Hugh and Mary were paid $2,700 for their claim, not quite the $3,310 they had hoped for.

Although they remained as teachers at Crow Creek, by January of 1865, Hugh and Mary were in Greenwood, South Dakota, trying to set up a new mission on the Yankton Reservation there. In the fall of 1864, the ABCFM Report for October 1865 informed readers that:

“Last autumn, Mr. C. endeavored to commence operations among the Yankton Dakota but there was not sufficient encouragement to justify an y considerable effort on their behalf as his services are not required – his connection with the Board has been terminated. He returns, however, with the respect and confidence of the committee.”[21]

Apparently Greenwood had not worked out as hoped. Thomas Williamson wrote in the Missionary Herald of 1865 that Hugh had suspended the school at Greenwood as of January 15 since the head chief is now a Romanist and there are French Romanists who have married Dakota women.[22]

Gideon Pond founded the Oak Grove Presbyterian Church in Bloomington, MN and Mary and Hugh Cunningham were members there in the last few years of Hugh’s life, even as they operated their own combined denominational church.

At some point after leaving the ABCFM in 1865, Hugh and Mary moved to Bloomington, Minnesota, where they eventually affiliated themselves with Gideon Pond’s Oak Grove Presbyterian Church. In the 1865 census they had three Dakota children living with them, Samuel, Mary and Jennie, and ten years later, in the 1875 census, Hugh is listed as a farmer in Bloomington.

By 1876, Hugh and Mary were the hosts of a combined denominational church and Sunday School in Bloomington. Hugh was the pastor of the Plymouth Congregational Church and he became superintendent of the Bloomington Ferry Church for twenty years while Mary taught the younger children. Preachers came from Oak Grove or Eden Prairie Methodist Church so they met at 2:30 p.m. on Sundays.

In the 1880 census Hugh and Mary are listed in Bloomington. Living with them are Fanny Stout, aged twenty. Fanny was Mary’s niece, the daughter of Mary’s oldest sister. Also with them is a boy named James Cunningham, aged ten, who is listed as an adopted son. I have not been able to determine if this James was Dakota or white, and his name only occurs in this specific census. In the Iape Oaye newspaper of July 1882, Mary B. Renville wrote that the Cunninghams were doing real home mission work and have one of the largest Sabbath schools and care for the loved ones. A large farm does not hinder them from doing Christian work.[22] The loved ones Mary refers to are likely Mary’s father, James Ellison, and Jane Williamson, who came from St. Peter to live with the Cunninghams at some point between 1881-1883.

By 1885, Hugh and Mary were living with Mary’s brother, William Ellison, and his family in Bloomington Ferry, Minnesota. William and his wife, Sarah Pond Ellison, built the Bloomington Ferry house. Their children living at home were Emma, 23; Sarah, 22; George, 19; Mary Margaret, 16; Esther, 15 and Ruth, 4. By that time, Jane Williamson had apparently moved to Greenwood, South Dakota, to live with her nephew, John Williamson, at the Yankton Reservation and James Ellison had passed away.

Hugh continued working with the church through Christmas of 1896 and passed away on January 17, 1897. His obituary, from the Cunningham family tree on Ancestry.com records the following:

“Cunningham-Hugh Doak, died on Sabbath morning Jan 17 at his home in Bloomington, Minn in his 75th year of age…The departed was one of the excellent of the earth. In early life he gave his heart to Christ, and united with the Presbyterian church in Ohio. He ever maintained a true and consistent Christian character. He gave forth in his life the unmistakable evidence of being one of God’s saints. He was preeminently a man of prayer. Prayer was his daily delight. He was an ardent lover and student of God’s holy word; it was his daily manna. He had a remarkably clear insight into its meaning. He loved the house of God and found a pure joy in her praises and worship. He was a most sincere and earnest servant of the Lord Jesus Christ. His life was devoted to the up building of his Master’s Kingdom on earth. The last twenty-one years of his life he was the faithful and beloved superintendent of a Sabbath-school near his home. He laid down the sacred office only three weeks before he entered upon his eternal rest and reward.

“In his death Oak Grove Presbyterian Church lost a valuable and much esteemed member and elder. He leaves in his world to mourn her loss, a dearly beloved wife, who for many years walked by his side in sweet and loving fellowship. May the God of all grace comfort her in this her great sorrow. ‘Precious is the sight of the Lord is the death of his saints.’ S.W.L”

After Hugh’s death, Mary moved to Humboldt, Kansas, where her brother John Ellison and his family were living. She spent the final years of her life with John and visited other family members in the south. On Sunday morning, February 18, 1906, she died at Denison, Texas, at the age of eighty-eight years. Her obituary tells her story:

Mary and Hugh were married for 39 years when Hugh died in 1897. Mary moved to Kansas to be near her brother John and his family and died there in 1906. She is buried in the Ellison family cemetery in Humboldt, Kansas.

“Mary B. Ellison was born May 2, 1817, in Adams county, Ohio. United with Presbyterian church when quite young. Married to H.D. Cunningham in Feb., 1857, and the next year they took charge of a boarding school for Indians, in western Minnesota, and continued in that work until the Mission was broken up in 1862. Then made Minneapolis their home until the death of Mr. Cunningham in 1898 [sic]. Since then Mrs. Cunningham has resided with relatives here at Humboldt and in the south. She died Sunday morning, Feb. 18, (1906) at Denison, Texas.

“The body was brought here (Humboldt, KS) and the funeral services were held at the Presbyterian church Tuesday at 10:30 a.m., Rev. R.C. McQuesten in charge. The interment took place in the Ellison cemetery, southwest of town.

“The deceased was a sister to J.C. Ellison and he has the sympathy of many friends in this affliction.

“Mr. and Mrs. J.C. Blair, of Denison, Texas, nephew and niece of the deceased, accompanied the remains to Humboldt.

“Humboldt Union

Feb. 24, 1906”

Like so many of their colleagues in the mission in Minnesota, the Ellisons and Cunninghams influenced not only generations of Dakota students but also left their mark on Minnesota.

[1] Thomas Williamson to S. B. Treat, April 19, 1848; Thomas Williamson to S.B. Treat, June 5, 1848; Samuel Pond to S.B. Treat October 20, 1848; ABCFM Corres., Box 1, MNHS.

[2] Jane Williamson to Elizabeth Burgess, June 9, 1848, Dawes Memorial Library, Marietta College, Item 15, Folder 2.

[3] Robert Hopkins to S.B. Treat, June 4, 1849; Samuel W. Pond to S.B. Treat, July 12, 1849, A Corres., Box 1, MNHS

[4] Maida Leonard Riggs, Editor, A Small Bit of Bread and Butter: Letters from the Dakota Territory 1832-1869, Ash Grove Press, South Deerfield, MA, 1996, p. 192

[5] The Cunningham’s experiences in the days following the beginning of the U.S. Dakota War on August 18, 1862, are well documented in Marjorie Emma Cunningham’s diary and in Hugh Doak Alexander’s written account of their escape. Neither one mentions that their sister Martha Ann Cunningham Rogers was in Minnesota when the war began. The only mention of her being there is that her trunk was lost during the escape. She and her husband are identified in the famous Adrian Ebell escape photograph of the Riggs Party but it really is unclear if she was actually in Minnesota at that time. The Cunningham family tree on Ancestry.com indicates that Marjorie and Hugh were definitely in Minnesota but doesn’t mention Martha.

[6] Alexander Huggins Journal, Huggins Digitized Collection, MNHS. Although Alexander Huggins doesn’t provide a first name for the Ellison boy, in John Ellison’s obituary in 1914 it mentions that he was not able to enlist in the Civil War because he had always suffered from eye problems so we may assume it was John who lost his glasses.

[7] Aiton Family Collection, Kaposia attendance roster, MNHS. I am not sure that the William Ellison listed on the roster is the William Ellison from Ohio. It was very common for the missionaries to give Dakota children the names of their own relatives as a way of honoring their family. The William Ellison at the school could be a Dakota boy.

[8] Jane Williamson to Elizabeth Burgess, November 29, 1852, Dawes Memorial Library, Marietta College, Item 19, Folder 3

[9] Stephen Riggs to S.B. Treat, March 4, 1856, ABCFM Corres, Box 1, MNHS

10 Ibid., June 12, 1858

[11] Mary Huggins Kerlinger Journal, p. 198; Huggins digitized collection, MNHS

[12] Hugh Cunningham to S. B. Treat, February 12, 1859, MNHS, ABCFM Corres. Box 1. Several of the missionaries were expressing concern about the ABCFM’s official position on slavery by this time. The mission board was very cautious about its donors and supporters in the south and how they might react to a strong abolitionist stance.

[13i] Thomas Williamson to S.B. Treat 7/28/1860 and 11/23/1860. MNHS, ABCFM Corres., Box 5. Annie Ackley’s story is told in a future Dakota Soul Sisters post.

[14] Marjorie Cunningham Diary, 1861-1863; October 28, 1861; NW Missions Manuscripts, MNHS P489. Readers who are interested in the details of the Williams family genealogy may want to note that William Stout, the young man who married Martha Williamson at Pejutazee in 1861, was the son of Mary Ellison Cunningham’s oldest sister, Kathryn Beauford Ellison Stout. William was Mary Ellison Cunningham’s nephew and he had come out to visit them at Hazlewood when he met Martha Williamson. Martha was only sixteen years old when she and William were married; William was twenty-two.

[15] Ibid.

[16] H.D. Cunningham Statement reproduced in A Thrilling Narrative of Indian Captivity: Dispatches from The Dakota War, by Mary Butler Renville, Edited by Carrie Rebar Zeman and Kathryn Zabelle Derounian Stodola, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 2012, pp. 192-197.

[17] Hugh Cunningham to S.B. Treat, December 1, 1862 and S.B. Treat to Hugh Cunningham, December 29, 1862, MNHS, ABCFM Corres., Box 7

[18] Hugh Cunningham to S.B. Treat, February 6, 1863; MNHS, ABCFM Corres., Box 7 and S.B. Treat to Hugh Cunningham, February 6, 1863; MNHS, NW Missions MS P489

[19] John Williamson to Thomas Williamson, July 7, 1863, MNHS, ABCFM Corres., Box 7

[20] John P. Williamson to Thomas S. Williamson, December 24, 1863, MNHS Williamson Papers, P726, Box 1

[21] AMCFM report for October 1865, MNHS, N.W. Mission MS P. 489, Box 21

[22] MNHS, Missionary Herald, 1865, p. 71. Romanists were members of the Roman Catholic church. In Hugh Doak Cunningham’s family tree on Ancestry.com, the reporter indicates that Hugh and Mary went to work with the Chippewa for two years, from 1865-1867. I have not been able to confirm that information.

[23] Mary B. Renville entry, Iape Oaye July 1882.