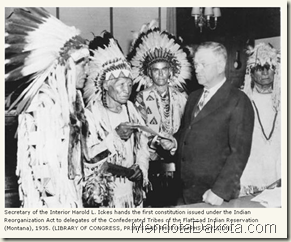

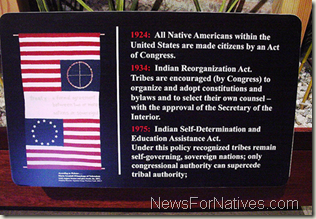

The Indian Reorganization Act of June 18, 1934, also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act or informally, the Indian New Deal, was a U.S. federal legislation which secured certain rights to Native Americans, including Alaska Natives.[1] These include a  reversal of the Dawes Act’s privatization of common holdings of American Indians and a return to local self-government on a tribal basis. The Act also restored to Native Americans the management of their assets (being mainly land) and included provisions intended to create a sound economic foundation for the inhabitants of Indian reservations. Section 18 of the IRA conditions application of the IRA on a majority vote of the affected Indian nation or tribe within one year of the effective date of the act (25 U.S.C. 478). The IRA was perhaps the most significant initiative of John Collier Sr., Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs from 1933 to 1945.

reversal of the Dawes Act’s privatization of common holdings of American Indians and a return to local self-government on a tribal basis. The Act also restored to Native Americans the management of their assets (being mainly land) and included provisions intended to create a sound economic foundation for the inhabitants of Indian reservations. Section 18 of the IRA conditions application of the IRA on a majority vote of the affected Indian nation or tribe within one year of the effective date of the act (25 U.S.C. 478). The IRA was perhaps the most significant initiative of John Collier Sr., Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs from 1933 to 1945.

The act did not require tribes to adopt a constitution. However, if the tribe chose to do so, the constitution had to:

1. allow the tribal council to employ legal counsel;

2. prohibit the tribal council from engaging any land transitions without majority approval of the tribe; and,

3. authorize the tribal council to negotiate with the Federal, State, and local governments.

Evidently, some of these restrictions were eliminated by the Native American Technical Corrections Act of 2003.[2]

The act slowed the practice of assigning tribal lands to individual tribal members and reduced the loss, through the practice  of checker boarding land sales to non-members within tribal areas, of native holdings. Owing to this Act and to other actions of federal courts and the government, over two million acres (8,000 km²) of land were returned to various tribes in the first 20 years after passage of the act.

of checker boarding land sales to non-members within tribal areas, of native holdings. Owing to this Act and to other actions of federal courts and the government, over two million acres (8,000 km²) of land were returned to various tribes in the first 20 years after passage of the act.

In 1954, the United States Department of Interior began implementing the termination and relocation phases of the Act. Among other effects, termination resulted in the legal dismantling of 61 tribal nations within the United States.

This act was based upon the thought that tribes should be in existence for an indefinite period of time.[3]

[edit] Constitutional challenges

The Supreme Court has been asked repeatedly to address the constitutionality of the IRA. In 1995, the Eighth Circuit declared the IRA unconstitutional.[4] The U.S. Department of the Interior sought U.S. Supreme Court review. The DOI then implemented new regulations and asked the U.S. Supreme Court to remand the case to the lower courts to reconsider their decision based on the new regulations. The U.S. Supreme Court Granted the petition, vacated the lower court’s ruling and remanded the case back to the lower court. Justices Scalia, O’Connor and Thomas dissented and stated that “[t]he decision today–to grant, vacate, and remand in light of the Government’s changed position–is both unprecedented and inexplicable.”  and “[w]hat makes today’s action inexplicable as well as unprecedented is the fact that the Government’s change of legal position does not even purport to be applicable to the present case.”[5] Seven months after the Supreme Court’s decision to grant, vacate, and remand, the DOI removed the land from trust. In 1997 the Tribe submitted an amended application to the Secretary, requesting that the United States take the land into trust on the Tribe’s behalf. The Eighth Circuit reexamined the constitutionality issue and affirmed the IRA’s constitutionality.

and “[w]hat makes today’s action inexplicable as well as unprecedented is the fact that the Government’s change of legal position does not even purport to be applicable to the present case.”[5] Seven months after the Supreme Court’s decision to grant, vacate, and remand, the DOI removed the land from trust. In 1997 the Tribe submitted an amended application to the Secretary, requesting that the United States take the land into trust on the Tribe’s behalf. The Eighth Circuit reexamined the constitutionality issue and affirmed the IRA’s constitutionality.

In 2008 Carcieri v Kempthorne was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court and was decided in 2009 as Carcieri v. Salazar[6]. In 1991, the Narragansett Indian tribe bought 31 acres of land. In 1998, the DOI agreed to take it into trust, exempting it from many state laws. The state believed that the tribe would open a casino or tax-free business on the land and sued to block the transfer, arguing that the IRA did not apply because the Narragansetts were not recognized by Congress as an Indian tribe until 1980.[7] The Supreme Court opined that the federal government could not place the Narragansett-owned 31 acres into trust because land was not recognized federally until after Congress passed the IRA in 1934.

In 2008, before the Carcieri opinion, in MichGO v Kempthorne, Judge Janice Rogers Brown of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals authored a dissent stating that she would have struck down key provisions of the IRA. Of the three circuit courts to address the IRA’s constitutionality, Judge Brown’s opinion is the only one to opine that the land-into-trust process violates the Constitution.[8] The U.S. Supreme Court did not accept the MichGO case for review. The First, Eighth and Tenth Circuits of the U.S. Court of Appeals have upheld the IRA’s constitutionality.[9]

Most recently, in a challenge to the U.S. Department of Interior’s decision to take land into trust for the Oneida Indian Nation, Upstate Citizens for Equality, New York State, Oneida County, Madison County, the town of Verona, the town of Vernon, and others argue that the IRA is unconstitutional.[10]

Most recently, in a challenge to the U.S. Department of Interior’s decision to take land into trust for the Oneida Indian Nation, Upstate Citizens for Equality, New York State, Oneida County, Madison County, the town of Verona, the town of Vernon, and others argue that the IRA is unconstitutional.[10]

[edit] Outcome

The act proved to be successful in conserving the tribal land base. However, it did not prove to be successful to the same extent when it came to self governing of the tribes.[11]

[edit] Notes and references

1. ^ Indian Reorganization Act, Encyclopaedia Britannica

2. ^ Native American Technical Corrections Act, 2003, The Orator

3. ^ Canby, William (2004). “American Indian Law”, p 24. ISBN 0314146407

4. ^ South Dakota v United States Dep’t of the Interior, 69 F.3d 878, 881-85 (8th Cir. 1995)

5. ^ Dep’t of the Interior v South Dakota, 519 U.S. 919, 919-20, 136 L. Ed. 2d 205, 117 S. Ct. 286 (1996)

6. ^ 555 U.S. ___ (Feb. 24, 2009)

7. ^ Carcieri at page 4 of opinion

8. ^ United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit MichGO v Kempthorne

9. ^ Carcieri v Kempthorne, 497 F.3d 15, 43 (1st Cir. 2007), overruled as Carcieri v. Salazar (U.S. Supreme Court); South Dakota v United States Dep’t of Interior, 423 F.3d 790, 798-99 (8th Cir. 2007); Shivwits Band of Paiute Indians v. Utah, 428 F.3d 966, 974 (10th Cir. 2005).

10. ^ Actual Complaint filed in court

11. ^ Canby, William (2004). “American Indian Law”, p 25. ISBN 0314146407

[hide]

v • d • e

Rights of Native Americans in the United States

Trials

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia · Worcester v. Georgia · Standing Bear v. Crook · Hodel v. Irving · Cobell v. Salazar · Talton v. Mayes · Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock

Acts

Indian Intercourse Act · Civilization Act · Indian Removal Act · Dawes Act · Curtis Act · Burke Act · Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 · Pueblo Lands Act · Indian Reorganization Act · Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act · Indian Civil Rights Act · Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act · Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act · American Indian Religious Freedom Act · Indian Child Welfare Act · Indian Gaming Regulatory Act · Indian Arts and Crafts Act · Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act · Native American Technical Corrections Act

Related

Public Law 280 · National Indian Gaming Commission · Native American gambling enterprises · Dawes Rolls · Bureau of Indian Affairs · Eagle feather law · Declaration of Indian Purpose

The Indian Reorganization Act of June 18, 1934. Originally added to our site on Feb 8, 2010..