Sharon Lennartson, tribal headwoman of the Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Community, exploded with joy when she learned of the Faribault Dakota Project in the works.

“I yelled and screamed to my boys, “Somebody’s finally going to listen,’” Lennartson recalls. I wanted every bit to be a part of it.”

In partnership with the Faribault Heritage Preservation Commission, Rice County Historical Society, Faribault Mural Society and Santee Sioux Nation, the Mendota Dakota Community will offer historical insight to a project that will honor the Dakotas’ impact on Faribault’s early years.

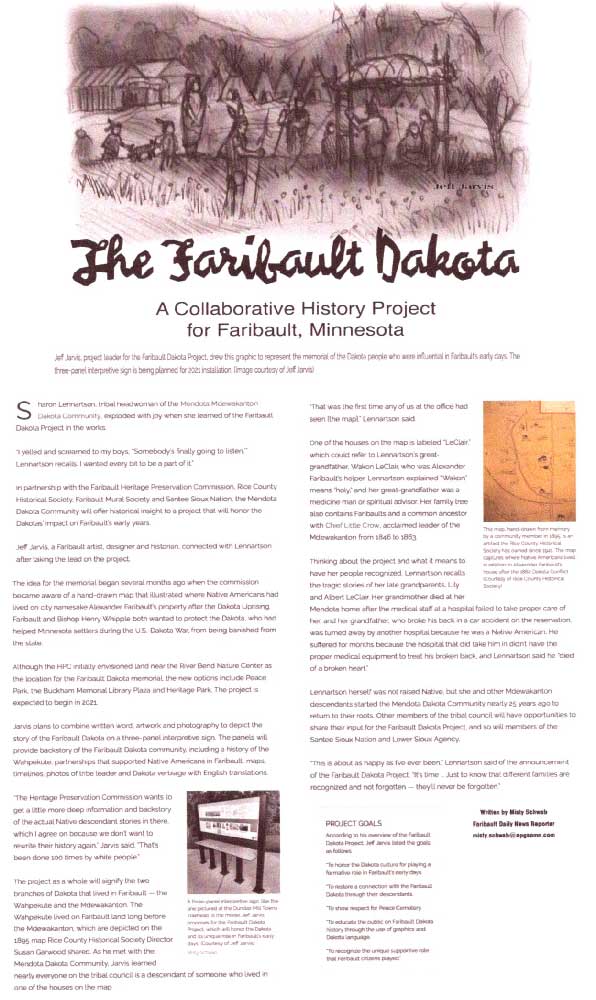

Jeff Jarvis, a Faribault artist, designer and historian, connected with Lennartson after taking the lead on the project.

The idea for the memorial began several months ago when the commission became aware of a hand-drawn map that illustrated where Native Americans had lived on city namesake Alexander Faribault’s property after the Dakota Uprising. Faribault and Bishop Henry Whipple both wanted to protect the Dakota, who had helped Minnesota settlers during the U.S.-Dakota War, from being banished from the state.

Although the HPC initially envisioned land near the River Bend Nature Center as the location for the Faribault Dakota memorial, the new options include Peace Park, the Buckham Memorial Library Plaza and Heritage Park. The project is expected to begin in 2021.

Jarvis plans to combine written word, artwork and photography to depict the story of the Faribault Dakota on a three-panel interpretive sign. The panels will provide backstory of the Faribault Dakota community, including a history of the Wahpekute, partnerships that supported Native Americans in Faribault, maps, timelines, photos of tribe leader and Dakota verbiage with English translations.

class=”inline-asset inline-image layout-vertical subscriber-hide tnt-inline-asset tnt-inline-relcontent tnt-inline-image tnt-inline-relation-child tnt-inline-presentation-default tnt-inline-alignment-default tnt-inline-width-default”>

class=”photo layout-vertical hover-expand letterbox-style-default”>class=”expand hidden-print”

class=”subscriber-preview”>

Sharon Lennartson, tribal headwoman of the Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Community, exploded with joy when she learned of the Faribault Dakota Project in the works.

“I yelled and screamed to my boys, “Somebody’s finally going to listen,’” Lennartson recalls. I wanted every bit to be a part of it.”

In partnership with the Faribault Heritage Preservation Commission, Rice County Historical Society, Faribault Mural Society and Santee Sioux Nation, the Mendota Dakota Community will offer historical insight to a project that will honor the Dakotas’ impact on Faribault’s early years.

Jeff Jarvis, a Faribault artist, designer and historian, connected with Lennartson after taking the lead on the project.

The idea for the memorial began several months ago when the commission became aware of a hand-drawn map that illustrated where Native Americans had lived on city namesake Alexander Faribault’s property after the Dakota Uprising. Faribault and Bishop Henry Whipple both wanted to protect the Dakota, who had helped Minnesota settlers during the U.S.-Dakota War, from being banished from the state.

Although the HPC initially envisioned land near the River Bend Nature Center as the location for the Faribault Dakota memorial, the new options include Peace Park, the Buckham Memorial Library Plaza and Heritage Park. The project is expected to begin in 2021.

Jarvis plans to combine written word, artwork and photography to depict the story of the Faribault Dakota on a three-panel interpretive sign. The panels will provide backstory of the Faribault Dakota community, including a history of the Wahpekute, partnerships that supported Native Americans in Faribault, maps, timelines, photos of tribe leader and Dakota verbiage with English translations.

“That was the first time any of us at the office had seen [the map],” Lennartson said.

One of the houses on the map is labeled “LeClair,” which could refer to Lennartson’s great-grandfather, Wakon LeClair, who was Alexander Faribault’s helper. Lennartson explained “Wakon” means “holy,” and her great-grandfather was a medicine man or spiritual advisor. Her family tree also contains Faribaults and a common ancestor with Chief Little Crow, acclaimed leader of the Mdewakanton from 1846 to 1863.

Thinking about the project and what it means to have her people recognized, Lennartson recalls the tragic stories of her late grandparents, Lily and Albert LeClair. Her grandmother died at her Mendota home after the medical staff at a hospital failed to take proper care of her, and her grandfather, who broke his back in a car accident on the reservation, was turned away by another hospital because he was a Native American. He suffered for months because the hospital that did take him in didn’t have the proper medical equipment to treat his broken back, and Lennartson said he “died of a broken heart.”

Lennartson herself was not raised Native, but she and other Mdewakanton descendants started the Mendota Dakota Community nearly 25 years ago to return to their roots. Other members of the tribal council will have opportunities to share their input for the Faribault Dakota Project, and so will members of the Santee Sioux Nation and Lower Sioux Agency.

The Mendota Dakota people have been in Minnesota for thousands of years, Lennartson said, and Dakota ancestors and descendants have been in Mendota for over 130 years. She and the others in the Mendota Dakota community are related to Chief Cetanwakanmani, Chief Taoyatwduta from the 1862 war, and Chief Wabasha as well as Agathe Winona Red Woman Angelique DuPuis Renville and Mazasnawin Iron Woman Rosalie Freniere. Some of their ancestors are from Little Crow’s village, Kaposia.

“This is about as happy as I’ve ever been,” Lennartson said of the announcement of the Faribault Dakota Project. “It’s time … Just to know that different families are recognized and not forgotten — they’ll never be forgotten.”

This story written by MISTY SCHWAB misty.schwab@apgsomn.com