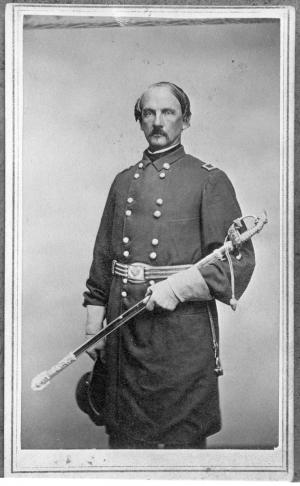

In 1834, Henry Sibley became a partner in the American Fur Company and settled in Mendota, Minnesota. Like a number of other traders, Sibley entered into a relationship with a Dakota woman, Red Blanket Woman. Their relationship produced a daughter, Helen Sibley, before the couple parted to live separate lives. Sibley acknowledged his daughter, protected her interests and education, and remained involved in her life. After the fur trade dwindled, Henry Sibley became a successful businessman, investing in lumbering, river transportation, railroads, and land. He played a pivotal role in the 1851 treaty negotiations and later commanded U.S. troops during the war and on the 1863 punitive expeditions. From 1867-70, he served as president of the Minnesota Historical Society.

During the war, Sibley was vilified in the press for his slowness in advancing to Fort Ridgely to liberate captive settlers. He wrote to his wife on September 4, 1862:

“I see . . . that the people are dissatisfied with my slow advance. Well, let them come and fight these Indians themselves, and they will [have] something to do besides grumbling. I have told Gov. R. in my dispatch that he can have my commission when he sees fit, as I would be too glad to let some one take my place. . . . I have not slept more than an hour in two nights, and have been in the saddle almost [all] of the time for two days and nights. . . .”

Colonel Sibley to Governor Ramsey, August 25, 1862:

“My heart is steeled against them, and if i have the means, and can catch them, I will sweep them with the besom of death.”

Sibley convened the military commission that condemned 303 Dakota men to death in the wake of the war.

Letter From Col. Henry Sibley to the Assistant Secretary of the Interior, December 19th, 1862.

“[I]t should be borne in mind that the Military Commission appointed by me were instructed only to satisfy themselves of the voluntary participation of the individual on trial, in the murders or massacres committed, either by voluntary participation of the individual on trial, in the murders or massacres committed, either by his voluntary concession or by other evidence and then to proceed no further. The degree of guilt was not one of the objects to be attained, and indeed it would have been impossible to devote as much time in eliciting details in each of so many hundred cases, as would have been required while the expedition was in the field. Every man who was condemned was sufficiently proven to be a voluntary participant, and no doubt exists in my mind that at least seven-eighths of those sentenced to be hung have been guilty of the most flagrant outrages and many of them concerned in the violation of white women and the murder of children.”